Last Tuesday was a bad day. I made a costly mistake, I was overtired. It was dark and rainy. I got ripped off, I felt like an idiot. I went home, curled into bed, and hated the world.

As I lay there, the dog jumped on the bed. I patted the mattress beside me, and over he crawled. He put his face right in my face, and I smelled his doggy breath and touched his floppy ears, and I thought:

“Bliss.”

I’ve had bad weeks, bad periods. Times where work is terrible, or I’m overlooked, or I’m taken advantage of. Times where I’ve been depressed or had a haunting suspicion that I was a terrible person, times where I’ve been a jerk, or I’ve angrily hissed at someone that they were a jerk, and I’ve wondered at how base we are.

And then there will be a moment where I see something happy or loving. Often, it’s the dog, with his little grunts and silky fur, but it can be buds of new growth on a tree, or the wedding band on Q’s hand – something little or simple like that. There is so much ugliness, and yet such beauty.

Last Wednesday night, I saw BigMouth, which is a one-man play involving speeches throughout history. Valentijn Dhaenens performs from a selection of great orations over the past two millennia, from Socrates to Osama Bin Laden and George W. Bush. The show was both excellent and thought-provoking. It covered the big themes: religion, death, slavery, race, power, justice.

I’ve read since that Dhaenens described the show as being about “human beings wanting to be a god”. The play opens with a speech from the Grand Inquisitor, one both inspiring and fanatical. If you know your history, you know that the Inquisition was a dark time, and that many were tortured for not complying with a certain set of beliefs. In the speech, there’s a hint of the zealotry that would have justified that torture.

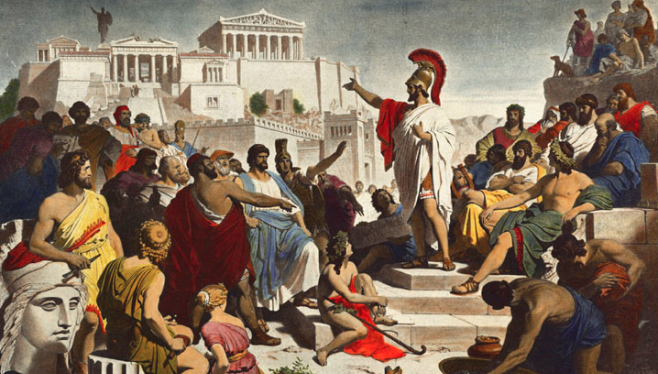

Many of the speeches had religious overtones, but many were speeches made during times of war, like Pericles’ speech to parents of dead soldiers from 400 B.C. after the Peloponnesian war. In a particularly interesting bit, Dhaenens performs excerpts from both Joseph Goebbels and George Patton, showing two very different styles of the war effort motivational speech.

Dhaenens, who is Belgian, performed some speeches from Belgian history, including one from the Catholic King Baudouin of the Belgians, who temporarily resigned to avoid signing the law that legalized abortion. In it, Baudouin speaks beautifully of the responsibility he felt to protect the lives of innocent unborn children. This not only is in sharp contrast to the war effort speeches, but also to a speech by Patrice Lumumba on the occasion of Congo’s independence from Belgium, which Baudouin attended. (Not a lot of respect for human life in the history of Belgians in Congo.)

I thought about the choices Dhaenens made when selecting the speeches, and about how much of them he enacted. Why Pericles rather than the Gettysburg address? Why only a line from FDR (“nothing to fear but fear itself”, attributed to George H.W.), but so much from Louis Farrakhan?

One speech, the statement from the wrongfully-accused Nicola Sacco (prior to his receipt of the death sentence), was performed almost in full. Only after learning more about his situation and reading the transcript, do I understand the choice: it was a speech from the oppressed.

Dhaenens set a tone with his selections, and the order in which they were performed, as he builds to the modern day. There is a calm excerpt from Bin Laden: “The events that affected my soul in a direct way started in 1982 when America permitted the Israelis to invade Lebanon and the American Sixth Fleet helped them in that… I couldn’t forget those moving scenes, blood and severed limbs, women and children sprawled everywhere”, contrasted with George W. Bush’s responses to Hurricane Katrina and Sept. 11, mentioning children of firefighters lost in the ruble, and that blood, those severed limbs.

A speech from Belgian politician Frank Vanhecke seemed prescient in light of some response to waves of migrants in Europe: his sweetly delivered fears of Europe becoming Muslim are given with a smile. For a viewer though, against the Bin Laden and Bush speeches, as well as the Lumumba independence speech, it’s impossible to reduce Vanhecke’s problem to a simple: “not in my backyard, let’s protect Europe”, without reflecting on the extent of conflict in the middle east, as well as struggles for independence in resource-rich places, and Bin Laden’s still-fresh quote about the remains of Lebanese children.

So yes: ugly, dark, difficult. The speeches deal with the worst parts of humanity – greed, slavery, vindication, retribution, racism.

And yet, how beautiful it is to learn, to try to understand another. How beautiful art is!

Highly recommended.