My husband watches the fights; I don’t. I went to join him once after he’d watched a set of UFC fights with friends, and caught the last one accidentally – I’d hoped to miss them all.

It was awful. So bloody. Seeing these young men give each other brain injuries for our enjoyment? It reminds me of To Kill a Mockingbird: “t’s morbid, watching a poor devil on trial for his life. Look at those folks, it’s like a Roman carnival”. We’re like the Roman throngs, watching the gladiators.

I can’t watch them without thinking: “It’s not rich boys getting into that ring.” As David Remnick writes: “Boxing has never been a sport of the middle class. It is a game for the poor, the lottery player, the all-or-nothing-at-all young men who risk their health for the infinitesimally small chance of riches and glory.”

The great boxers, the ones we think of – Smokin’ Joe, Sugar Ray (Leonard and Robinson), Mike Tyson, Jack Johnson, Joe Louis – these are not men who had a lot of options; these are men who used their fists to punch themselves out of abject poverty.

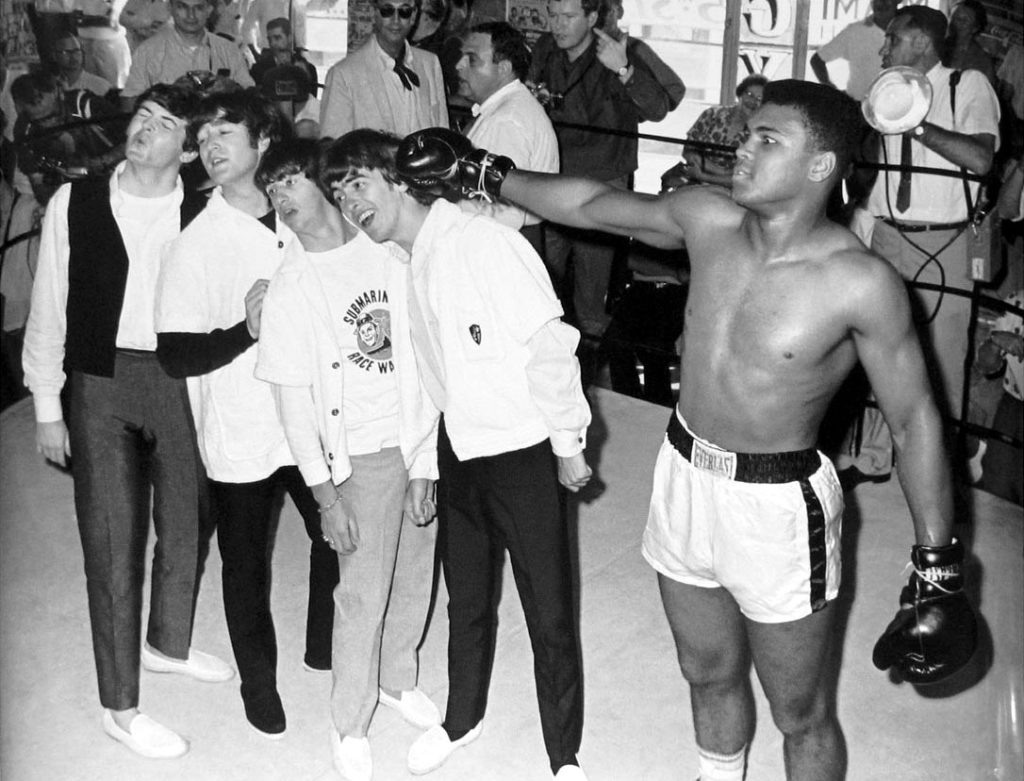

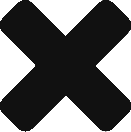

And yet, that’s what makes the sport so enthralling, what makes these men legends. It is a sport for individuals: there are two men in that ring, and one winner, and the winner wins on his own two feet. He has trained; he has forced his body into its condition; he has overcome. To be a champion? He has won many, many fights – not just against his opponents, but against that poverty. That’s part of the appeal, I think: the mythology of those legends, and seeing them develop that mythology over the fights themselves. Mayweather vs. Pacquiao, Tyson vs. Holyfield (Jesus H. Christ, what a fight that was!), Ali vs. Frazier (every time): all huge fights. At the risk of sounding like a sports writer, some of the fights were downright world-changing: Louis vs. Schmeling, Johnson vs. Jeffries – those made Louis and Johnson heroes. Those men were larger than life.

“People say I talk so slow today. That’s no surprise. I calculated I’ve taken 29,000 punches. But I earned $57 million and I saved half of it. So I took a few hard knocks. Do you know how many black men are killed every year by guns and knives without a penny to their names? I may talk slow, but my mind is OK.” – Ali, January 20, 1984.

Muhammad Ali did not grow up as poor as Smokin’ Joe Frazier. Muhammad Ali did some despicable, racist things – including to Smokin’ Joe.

But Muhammad Ali also spoke about important things. Muhammad Ali asked us to think. He challenged not just his opponents, but all of us. Remnick wrote last week:

Ali was not blind to the hypocrisies and brutality of the “game” that had been his professional life. The source of his fame was a sport in which race was often an ugly element of its history, a contest in which one man tries to beat another senseless, tries to inflict temporary brain injury (a knockout) on another. Ali reaped millions of dollars from the fight game, and yet he was, at times, ambivalent about that history and the lurid spectacle of one man fighting another, particularly one black man fighting another. Ali had the capacity to enjoy the fruits of the game and the riches it brought, but he also knew the history of the sport—John L. Sullivan refusing to fight black challengers and Jim Jeffries telling the world he would retire “when there are no white men left to fight.” Ali was schooled in the history of Jack Johnson’s pride and persecution—the band at ringside struck up “All Coons Look Alike to Me” when Jeffries finally dared to face Johnson. He knew well how Jack Dempsey avoided black fighters after taking the title. Ali had seen how fighters before him had been sponsored, managed, and exploited by Mafia thugs. He remembered from childhood how Joe Louis’s handlers gave him a set of rules to avoid alienating white America.

“They stand around and say, ‘Good fight, boy: you’re a good boy; good goin’,” Ali said, in 1970. “They don’t look at fighters to have brains. They don’t look at fighters to be businessmen, or human, or intelligent. Fighters are just brutes that come to entertain the rich white people. Beat up on each other and break each other’s noses, and bleed, and show off like two little monkeys for the crowd, killing each other for the crowd. And half the crowd is white. We’re just like two slaves in that ring. The masters get two of us big old black slaves and let us fight it out while they bet: ‘My slave can whup your slave.’ That’s what I see when I see two black people fighting.”

If that’s not a challenge, I don’t know what is. Brilliant, great, Muhammad Ali.

Muhammad Ali could be cruel, he could be full of rage – as when he fought Ernie Terrell, who’d called him Cassius Clay – pummeling him while yelling: “What’s my name?” We talk about Ali in the language of greatness: his stance on Vietnam and his sacrifice; his poetry; his name change – he was exceptional.

But it cannot be ignored that some of his greatness comes from having been an exceptional fighter (and not an exceptional loser), and some of his mythology comes from having done things like broken a vein in Ernie Tyrell’s eye while taunting him, or downing the giant Sonny Liston.

I read that, while writing the Game of Thrones books, George R.R. Martin thought a lot about power – about kingmaking, throne-taking, and the dark side of that, which is killing, death and bloodshed.

Muhammad Ali, and the great fighters, they remind me of that: that we see power in strength, and in brutalization – in that bloodshed.

Perhaps I’m wrong to loathe the fights: instead of seeing them simply as events where these two boys whup each other to brain damage for our enjoyment, it’s also that we pay to see them fight because we want to witness their greatness and their power.

I can’t shake that that power, what we seek – it’s rooted in violence.